Umberto Eco’s The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana is a mishmash of high and pop culture, and I wish it were more a mishmash of action and philosophy. Instead, the latter predominates, and the “novel” becomes a mediation on the nature of memory with only incidental, minimal plot. The obvious comparison is to Proust, who Eco alludes to or references at least several times that I caught and probably more that I didn’t. The comparison is not flattering for Eco, however, and I can’t help but like the precision and the depth of Proust over the comic book and literary metaphors used by Eco. Long descriptions of books and records jar me from what story of Yambo I try to find and grasp. Yes, I understand that I’m supposed to be following his story through the stories he inhabited as a child, but the device too often became tedious instead of enlightening.

The novel starts with the scattered observations of Yambo as he returns to consciousness, and at first we get a stream of his impression. Then the narrative takes on some of the traits of a conventional, structured first-person perspective, dipping in and out of descriptions of comics, books, and politics, until it descends again into a hallucinatory realm as Yambo plunges back toward the memories he has forgotten. In this dreaming coma it is hard—intentionally so, I’m sure—to follow what happens, and in time I gave up the attempt to follow the narrative thread as images and disjointed philosophy became everything.

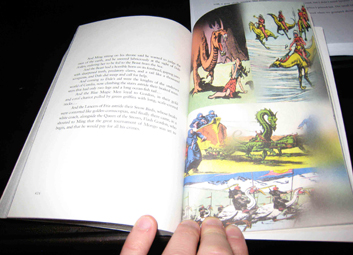

The division between life and books, whether comic or otherwise, breaks down toward the final pages, as heroes and villains from comic books (sometimes literally depicted, as shown in the image below) become symbols in Yambo’s struggle to regain the memory of the distant Lila. His banal schoolboy infatuation becomes the focus of the struggle that plays out against comic book characters, and he realizes that he has been searching for Lila for his entire life—she is the eternal feminine. I’m not sure that I buy this yearning; in a writer like Robertson Davies, it would be seen in retrospect as suspect or fleeting, as the feelings of David Staunton are, or those of Dunstan Ramsay with Diana. For Yambo, the memory is everything, but its pursuit through the perpetual obsession of symbols/people who define life grows tired, especially because Yambo does not recognize that he lets himself be defined by these ludicrous characters. The power of the comic book characters is not truly being able to fly and such, but in their ability to reflect the reader back, who, in this case, is Yambo, and he in turn reflects us.

All very clever, but also rather irritating, especially with the comic art depicting the struggle. Maybe my criticism is unfair, as I just read The Name of the Rose and it is not really fair to hold a regular novel, even a literary one, against a masterpiece. So I cannot blame Eco, as his early novel sets the bar too high for The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana. Towards the end I also see how the blurbs chosen for The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana’s jacket work: The Sunday Times writes that “As always with Eco, there is much to admire,” but perhaps some not to be admired, and the Observer writes that The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana “confirms Eco as an outstanding writer of philosophy dressed fiction.” The dressing is too flimsy for the fiction section.

I also have to compare The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana to Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red, as I read them back-to-back and both are obsessed with memory and meaning to an almost Proustian degree. I don’t recommend the two consecutively, and I ended up with them thanks to more bookstore oddities.

Both novels also implicitly ask how we know what we know. My Name is Red has characters who constantly refer to “common knowledge” that is anything but common and to whether they will be remembered; Shekure, the vain woman, says that “[…] Perhaps one day someone from a distant land will listen to this story of mine,” though later in the same paragraph she says, “If I happen to tell a lie or two from time to time, it’s so you don’t come to any false conclusions about me.” Marlowe of Heart of Darkness is a better liar and the amnesia of The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana a better dissembler, but all three tell as much about telling tales as they do about the tale itself through the way they seek memory. But Heart of Darkness has something the other two lack: a strong, consistent narrative drive. My Name is Black doesn’t have one by its multiple-perspective design, which becomes disorienting, as though the reader needs to understand not just the murder or clues to the murder but who is speaking and giving the murder. It gave me a sense of vertigo I didn’t like, but My Name is Black also has the sense of a novel that will satisfy much more the second time around, like Faulkner. So try it and Heart of Darkness and The Name of the Rose, but let Loana remain mysterious.